7. Captivating Reality and Scientific Abstraction

Lois Dodd, Terry Winters, Alex Katz and Jiří Georg Dokoupil

Lois Dodd, Terry Winters, Alex Katz and Jiří Georg Dokoupil

Audio recording

Audio transcription

Surrounding the central sculptures are four paintings that oscillate between documentations of reality and abstractions created scientifically. The following explanation will move back and forth between the works, discussing the connections as opposed to a linear narration.

The lively blue sky of rural mid-coast Maine is reflected in Lois Dodd’s 1979 painting of a closed window. The same beauty of a clear, vivid sky showcased in Alex Katz’s 1976 painting, frames a young woman atop a horse at his summer home in Maine. Contemporaries at Cooper Union, Lois Dodd and Alex Katz, who are both still alive and painting at 95 and 94 years old, respectively, shaped the postwar Modern art scene in New York City and coastal Maine. Dodd and Katz painted in response to their surroundings; capturing elements of architecture, cityscapes, people, and nature, which contrasted with the popular, non-objective Abstract Expressionism of the mid-twentieth century.

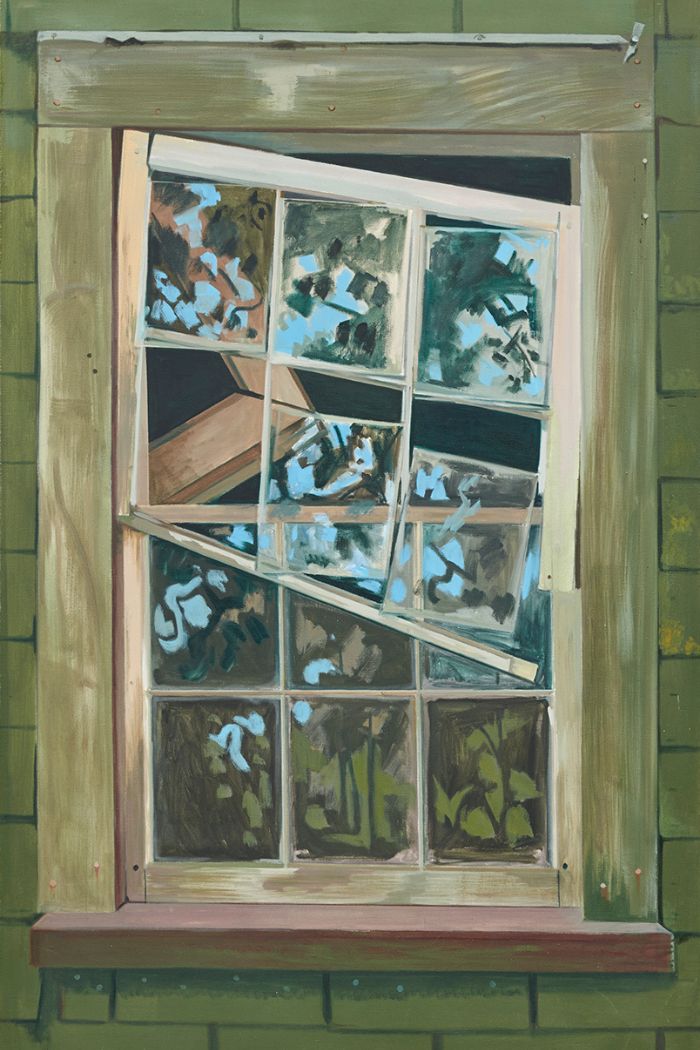

For over Fifty years Lois Dodd has painted her everyday surroundings where she lives and works – New York City’s Lower East Side, rural Maine, and the Delaware Water Gap. Dodd’s intimately-scaled paintings are almost always completed in a single plein-air sitting—which is the act of painting outdoors. Searching out the underlying geometry and life of New England buildings and landscapes, Dodd details the beautiful specificities of lush summer gardens, dried leafless plants, nocturnal moonlit skies, and views of windows. She often returns to familiar motifs repeatedly at different times of the year with dramatically varied results. In her studies of windows, Dodd finds great inspiration within this steady geometric structure, where color and movement are set free in the reflective surfaces. In Blue Sky Window, shadows play across the window’s white frame in rose gold and gray, making the perceived stillness of the blue sky an illusion. In contrast to this serene geometry, Dodd’s second painting across the gallery, Falling Window Sash, painted about two decades apart, illustrates the effects of time on abandoned architecture.

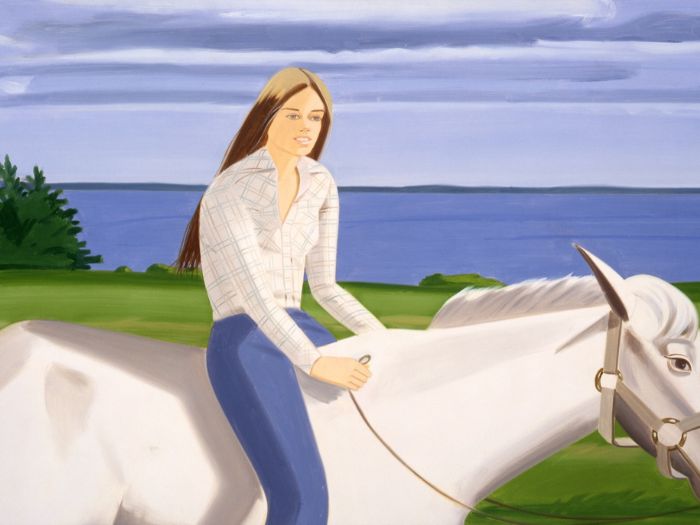

In his figurative painting, Jean on Horse, situated between two categorically abstract paintings, Alex Katz flirts with the line between realism and abstraction. Emerging as an artist in the mid-twentieth century, when much of American art had turned away from representation, Katz forged a mode of figurative painting that fused the energy of Abstract Expressionism with the American vernacular of magazines, billboards, and movie screens. Although based in New York, Katz paintings often depict scenes of a well-heeled leisure society, almost exclusively presenting friends, literary figures and those of his art world circles, within the landscape of Maine.

Friend of Vincent Katz (the artist’s son), Jean was a neighbor of the Katz family. Having only painted a few works with animals in his career, Jean and her horse appear in several of Katz’s paintings from 1976. What is special about this work is that Katz asked his son to take a photograph of Jean while on the horse as he painted their portrait. The master of vivid color wanted to compare the difference between the colors of the photograph to the ones of his painting, concluding that the colors of his painting were much stronger.

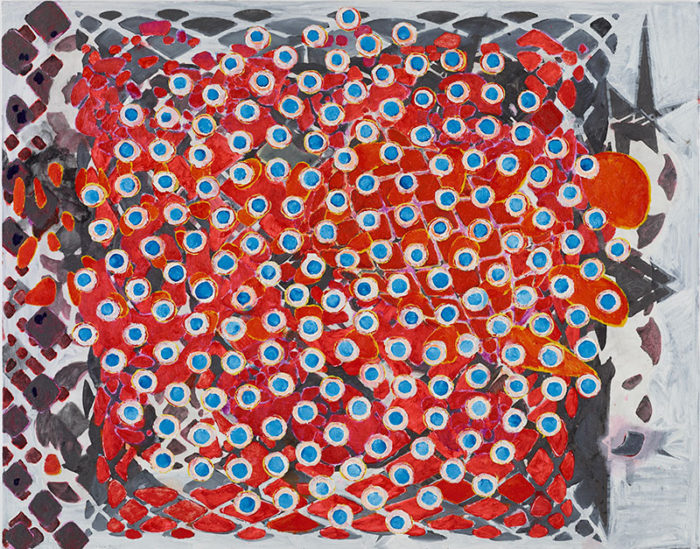

Between Jean on Horse and Blue Sky Window sits the flowering, piercing blue circles of Cobalt (Blue) by Terry Winters. Surrounding each cobalt dot, white and yellow paint form imperfect concentric circles that penetrate through the bright red shapes in the midground of the painting. Mirrored by grayscale patches, the logic of the patterns breaks away around the edges of the canvas. Weaving together various elements, the work combines free painterliness with rational structure. Many of Winters’ earliest works depict organic forms reminiscent of botanical imagery. Over time, Winters’ range of themes expanded to include the architecture of living systems, mathematical diagrams, musical notation, and new orders of data visualization. Between 2011-2013, Winters found deep connection to Austrian philosopher Karl Popper’s 1966 essay, Of Clocks and Clouds. In his essay, Popper divided all observable phenomena into two categories: one comprises mechanisms of precise and determinant function (clocks), while the other operates under indeterminate and extraordinary conditions (clouds). For Winters, the combination of these classifications resonated in regard to painting. Cobalt (Blue) is an exciting fusion of conscious composition and color fields generated by free brush strokes.

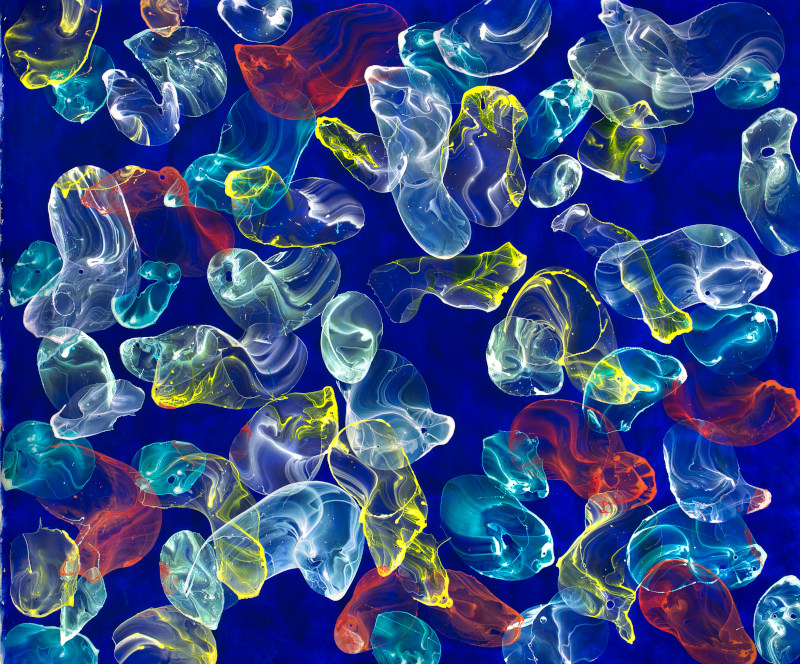

Similar in color palette to Winter’s Cobalt (Blue) but deviating in process, Jiří Georg Dokoupil’s Untitled #4 contains an electrified blue backdrop for white, red, yellow, and cyan dragged iridescent bubbles. For his Soap Bubble Painting series, Dokoupil pops cosmic bubbles of suspended pigments in soap-lye across his canvas. Dokoupil has not used a paintbrush since the 1980s and instead experiments with various tools for mark-making such as whips and rolling tires onto his surface of choice. In doing so, he deliberately removes the brushstroke or evidence of the artists’ hand from the act of painting. Rather, the artist has developed a catalogued body of more than one-hundred different styles and techniques that he chooses through a systematized approach that removes notions of distinctive, personal expression to avoid having any sort of singular aesthetic. In this method of making, he seeks to explore understandings of authenticity. Seen here in Untitled #4, Dokoupil moves effortlessly between the realms of the artistic, technical, and scientific.